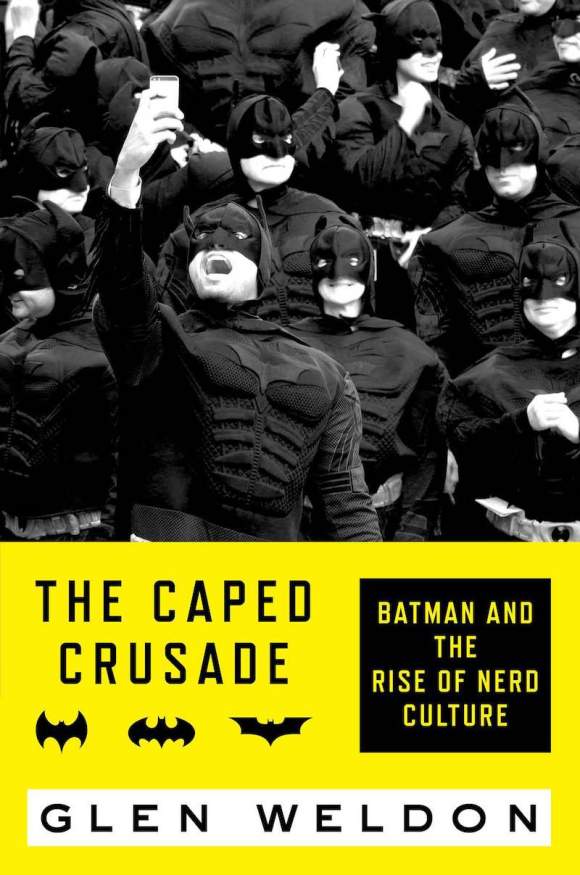

While everyone knows the story of how Bruce Wayne became Batman, not everyone knows the real-life story of how the character has morphed over the years into the one we see today in movies, video games, and comic books. But in new book, The Caped Crusade: Batman And The Rise Of Nerd Culture (hardcover, digital), writer Glen Weldon doesn’t just explores the character’s durability and mutability, he also widens his scope to examine what Batman’s durability and mutability says about our modern culture.

photo credit: Faustino Nunez

I always like to start at the beginning. So, what is The Caped Crusade: Batman And The Rise Of Nerd Culture about?

It’s a deep dive into the character’s history, but it’s more than that because I already did that with superman [Superman: The Unauthorized Biography], so I widen out from that to talk about the rise of nerd culture. Batman is a good lens to look at the rise of nerd culture because he is a nerd. There are other superheroes who are nerds, Spider-man is a nerd, but Batman is different because he’s obsessed, and it’s that obsession, I argue in the book, that makes for the kinship that we nerds feel with him.

When Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams remade the character in 1970 pretty much from scratch, which they had to do to distance themselves from the ’66 television show, they basically found something new about the character. They went back to Batman’s origin, to something that had just been dealt with as a plot point for most of his life, which was his oath, the fact that he swears an oath to wage war on criminals. Every hero had an oath like that back then, but they realized that comic readers had changed, had gotten slightly order, and were teens and adults, and so to speak to them, you have to speak about something they know about. So that obsession set up a sympathetic resonance with Batman’s fan base. And it’s why we’re still talking about him today.

While The Caped Crusade: Batman And The Rise Of Nerd Culture is non-fiction, it doesn’t strike a completely serious, academic tone, though it’s not jokey. Is that just your natural style, or did you think this would be read more by comic book fans than people interested in sociology?

No, it’s where I come at it from. I’m not a historian and I’m not necessarily a journalist. I’m a critic and that means I’m supposed to be engaged in figuring out why a Batman story works and why it doesn’t. The thing is, when you do a deep dive like this, it can feel like a term paper, so you need to inject something — in my case, it’s a sense of humor — to keep people engaged.

As for who the audience may be for this book, I hope it’s for both “nerds and normals,” as I said in the book. What I can bring to the normal is a good grounding in how the world change, how nerd culture has become so pervasive. And what I can bring to the nerd is some insight and make observations that may not have occurred to them. I’m trying to split the difference.

The thing that I noticed was that the funny stuff seemed all to be in the footnotes. Which reminded me of what Mary Roach does in her books Bonk, Gulp…

Oh, I know her work well. And David Foster Wallace used to do great stuff with footnotes as well. It’s a fun device.

Right. But I was wondering why you did it this way?

Well, there are a lot of jokes in the main text. But a lot of it was my editor saying, “This sentence already has a lot of subordinate clauses, and if you keep them all in, you’re going to have page long paragraphs.” And I realized that because I just read the book for the audio book, and the next book is going to be more Hemingway, short declarative sentences, and less Virginia Woolf on crack.

Now, you live in Washington D.C. Was there every any thought of having this book be more about politics, about Batman as vigilante? Because you do mention the shooting that happened at the theater in Colorado when The Dark Knight Rises opened.

Oh, it’s just not my grounding. If I’m anything, I’m a literary critic and a cultural critic. There’s also books like that already. Will Brooker did a couple books on Batman in the twenty-first century [Batman Unmasked: Analyzing A Cultural Icon and Hunting The Dark Knight: Twenty-First Century Batman], and it just felt like it was territory that had been covered.

In researching this book, did you learn anything that really surprised you?

I spoke to Dean Trippe, who wrote this amazing webcomic called Something Terrible, which was about how Dean, as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, saw Batman as someone who had something shattering to him and dedicated himself to others, to being of use to others. In a way, what Batman did, by making this oath to spend the rest of his life fighting criminals, that’s an act of self-rescue. I hadn’t really seen Batman like that before. And the more I looked at it, the more I saw that if you just think Batman is a bad ass who can beat people up, you’re missing something fundamental about the character, that he’s not a creature of rage but a creature of hope. It’s a weird hope, a Sisyphean hope, but that’s hugely important to who he and what he stands for.

You’ve written books about Superman and Batman. Does that mean you’re planning to do a book about Wonder Woman next?

No, there’s already some good books about Wonder Woman. With The Caped Crusade, I started to pivoting away to talk more about the culture that surrounds the character, and that’s where my interest lies now. So I think the next thing, if I get the opportunity, will be an even wider perspective. Maybe on nerds, maybe on things nerds love, I don’t know.